Executive summary

NEXUS (born as “KMS”) set out to solve a stubborn problem at Method: as the company crossed ~300 people, high-value work scattered across tools and teams, and institutional memory lived in people’s heads. We didn’t need another place to store files; we needed a way to make the right artifacts obvious, trustworthy, and re-usable. The residency’s first half was intentionally research-heavy—interviews, surveys, workshops, landscape analysis—while engineering remained in an exploratory posture. At roughly week five, we flipped into build mode. I stepped in as Technical Manager, bootstrapped the repo and stack, recruited a junior team off another project, and led two back-to-back sprints to land an MVP: Google SSO, faceted search with cards/list views, opinionated upload/curation, bookmarks, and a chat surface. The path wasn’t linear: we initially recommended a Chrome extension, then pivoted to a web app due to design constraints, talent fit, and long-term extensibility. We shipped; we learned; and we wrote down what we’d do differently.

Origin story: research first, code later

The first five to six weeks belonged to Design and PM. They ran discovery properly: in-depth user interviews and surveys, co-creation workshops, taxonomy work, and a tool landscape scan. That front-loaded clarity—shared language around clients ↔ projects ↔ phases ↔ content types—and it built conviction that “drive-by uploading” without curation would just produce a new heap. The cost of that focus, in a nine-week program, is obvious in hindsight: build time collapses.

Midway through, two engineers (myself and Shloka Gupta) were still exploring options. Momentum felt thin. To reframe the conversation, I built a Google Workspace Add-on in under 24 hours. That meant standing up a GCP project, OAuth, Drive APIs, Gemini, a Google Apps Script codebase, and packaging the add-on—net new for me. The prototype did what prototypes should: it lit a fire. It showed the shape of the product and pulled the team out of analysis loops. Around then, Shloka nominated me to take on Technical Manager for the 13-person team—all interns in Method’s summer residency program.

The pivot: extension on paper, web app in practice

As Technical Manager, I conducted a comparative analysis of implementation approaches, evaluating browser extensions, web applications, and hybrid solutions against our constraints and goals. The analysis pointed to a Chrome extension as the optimal path: operate in-flow inside Drive, minimize context switching, and ship fast. Design pushed back—hard—for good reasons. Injecting UI into Drive’s DOM limited creative freedom and came with fragility risk when Google changes markup. Meanwhile, the engineers we could recruit on short notice had web-app experience, not extension experience. We also knew we’d want to index beyond Drive (Figma, Miro) post-MVP.

So we pivoted to a standalone web app: Next.js + Firebase, Google sign-in, opinionated curation, and deep links back into source systems. The call happened quickly (faster than I liked—the pivot surfaced in a live meeting before we synced), but the rationale was sound. Even with seasoned extension devs, Design’s constraints and the multi-source roadmap still favor a decoupled surface.

Engineering spin-up: from blank repo to running product

When I assumed the TM role (around week five), there were effectively two engineers and no code we intended to keep. With just four weeks remaining, we needed a production-ready foundation immediately—no time for iterative architecture decisions or gradual team onboarding.

Rapid infrastructure bootstrapping

I made the strategic decision to front-load all foundational work myself, creating a complete development environment in the first week. This meant building everything from scratch: a Next.js 15 + TypeScript scaffold, Tailwind styling system, ESLint/Prettier configuration, Node 20 setup, Husky pre-commit hooks, Firebase Hosting config, NextAuth Google provider integration, and comprehensive documentation including onboarding guides, environment setup, and operational runbooks.

The result was ~40k lines of foundational code that gave incoming engineers a fully functional starting point rather than configuration overhead. We deployed to Firebase Hosting for a static, zero-ops footprint that the team could iterate on without infrastructure concerns.

Then we hit our first major technical wall. I briefly adopted the googleapis Node.js SDK, thinking it would simplify Drive integration. Instead, it required server-side execution and broke our static build process entirely. We scrambled to migrate to Vercel for its seamless server functions support, but that decision cascaded into new problems: organization permission conflicts blocked deployments, our zip-file repo migration fragmented Git history, and silent deployment failures ate hours of debugging time. I found myself troubleshooting org-specific Vercel configurations instead of building features.

The breakthrough came from embracing constraints rather than fighting them. We dropped the googleapis SDK entirely and called Drive’s REST endpoints directly from the browser, eliminating server dependencies and restoring our zero-ops deployment model. The lesson became clear: when facing time pressure with an intern team, align your architecture with your infrastructure constraints rather than forcing infrastructure changes to accommodate theoretical best practices.

Meanwhile, I recruited six engineering interns from another residency project (Tech Dash). That’s more hands than I wanted, but managing a team of interns was a valuable learning experience. The reality: velocity was fastest for anything I built myself; the interns scaled only after I invested heavily in guardrails (lint/type checks, pre-commit), pairing sessions, and detailed PR reviews. CI did block merges (Cypress smoke test, lint, type-check), but too many PRs failed and I often fixed the failures myself rather than sending them back—with only 3 weeks to build, it was faster for me to resolve linting/type issues (often with AI assistance) than wait for interns to debug them. Under extreme time pressure with inexperienced developers, this was probably the right call, though it meant less learning opportunity for the team.

User experience: what it feels like to use

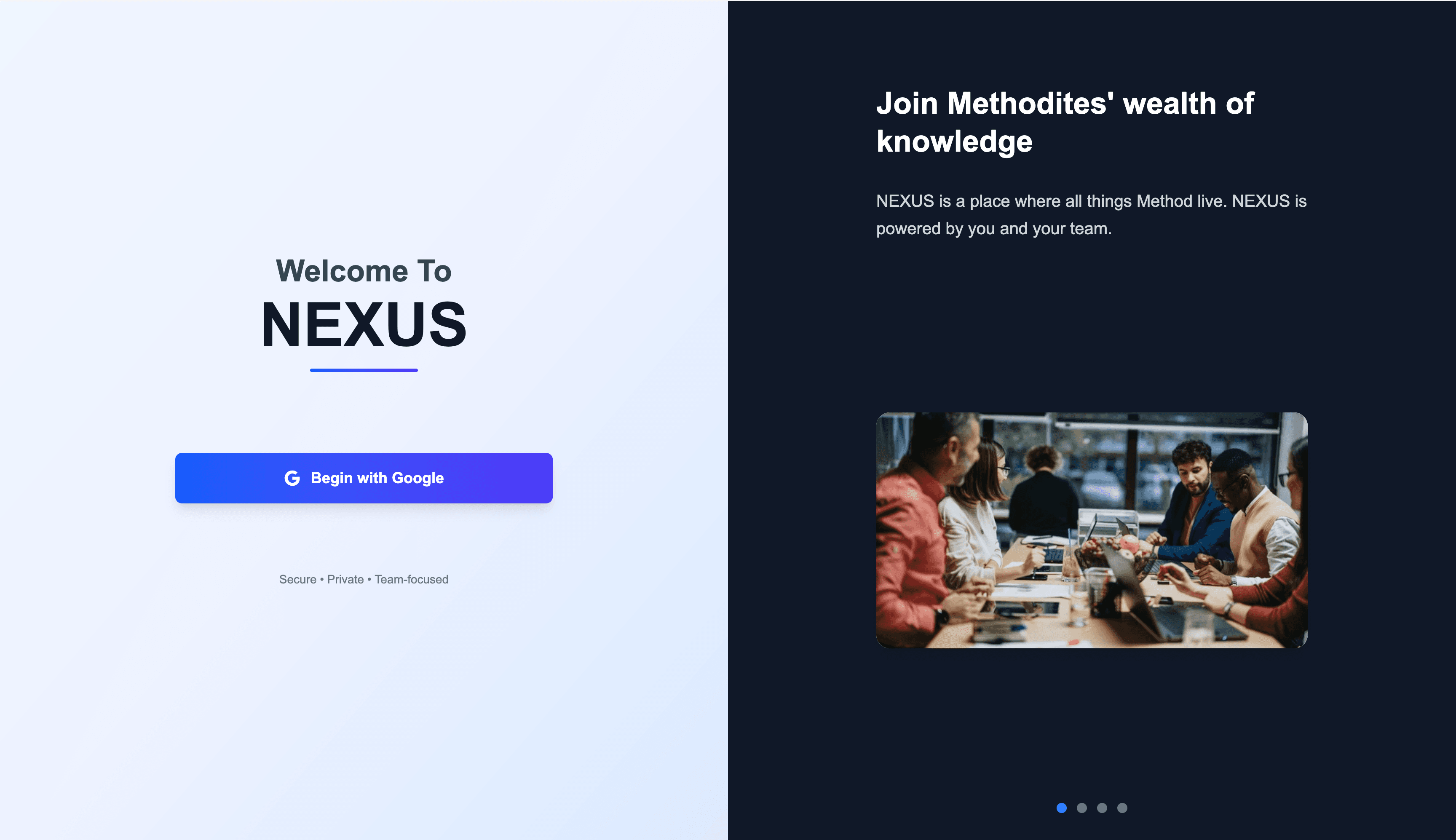

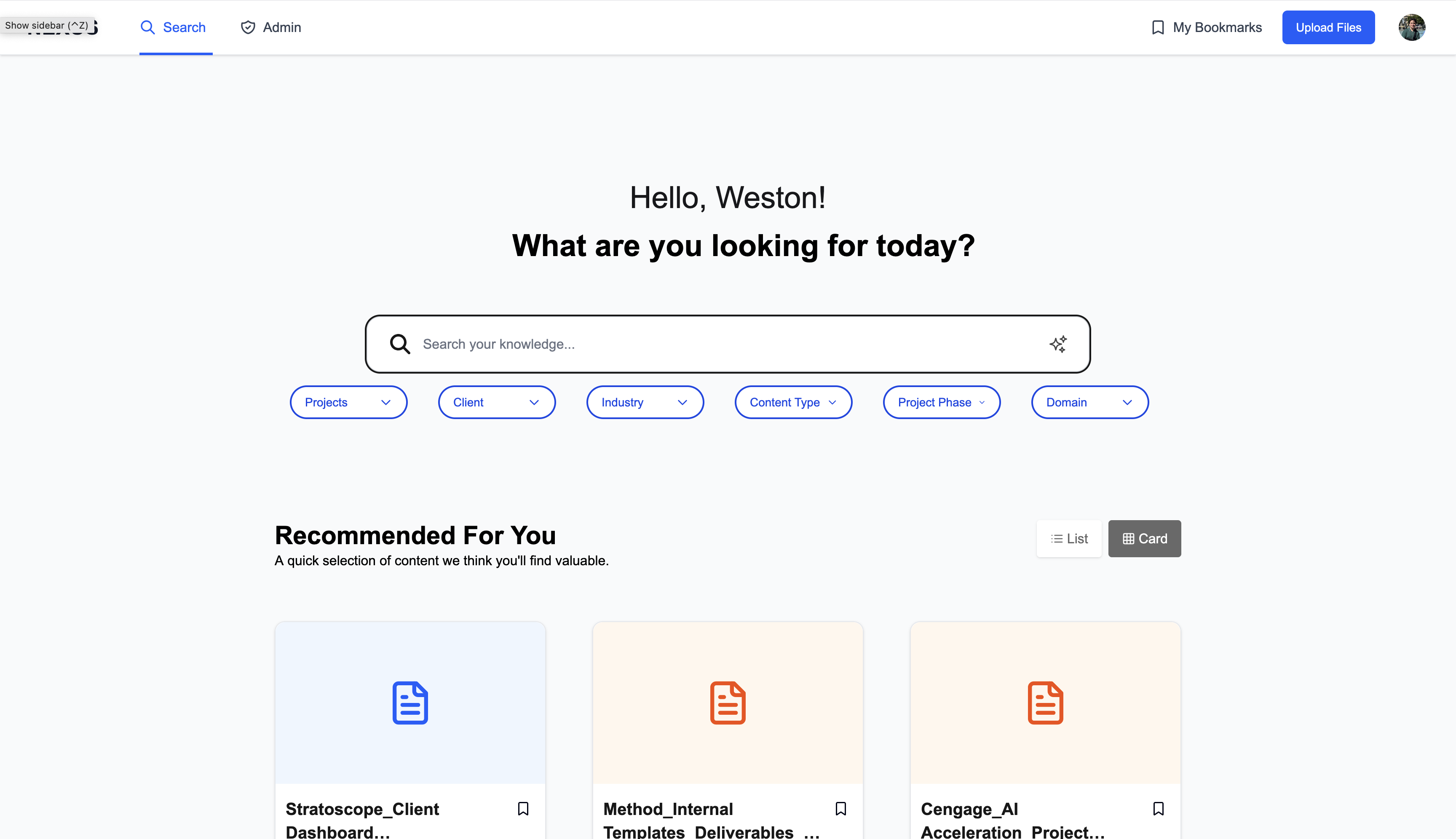

Login & onboarding

You arrive on a clean, split-screen interface. The light panel offers “Begin with Google”—one-click authentication that gets you started immediately.

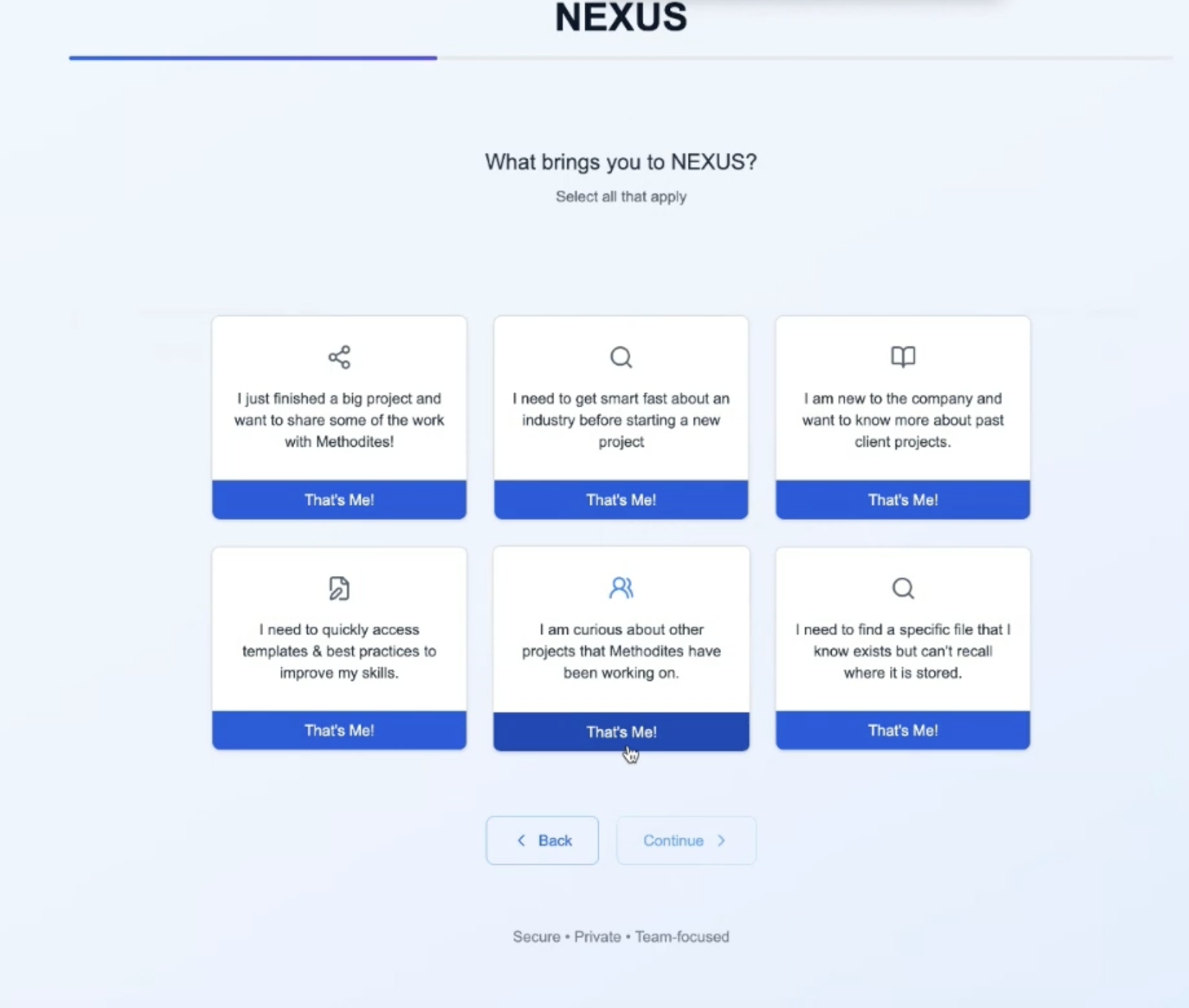

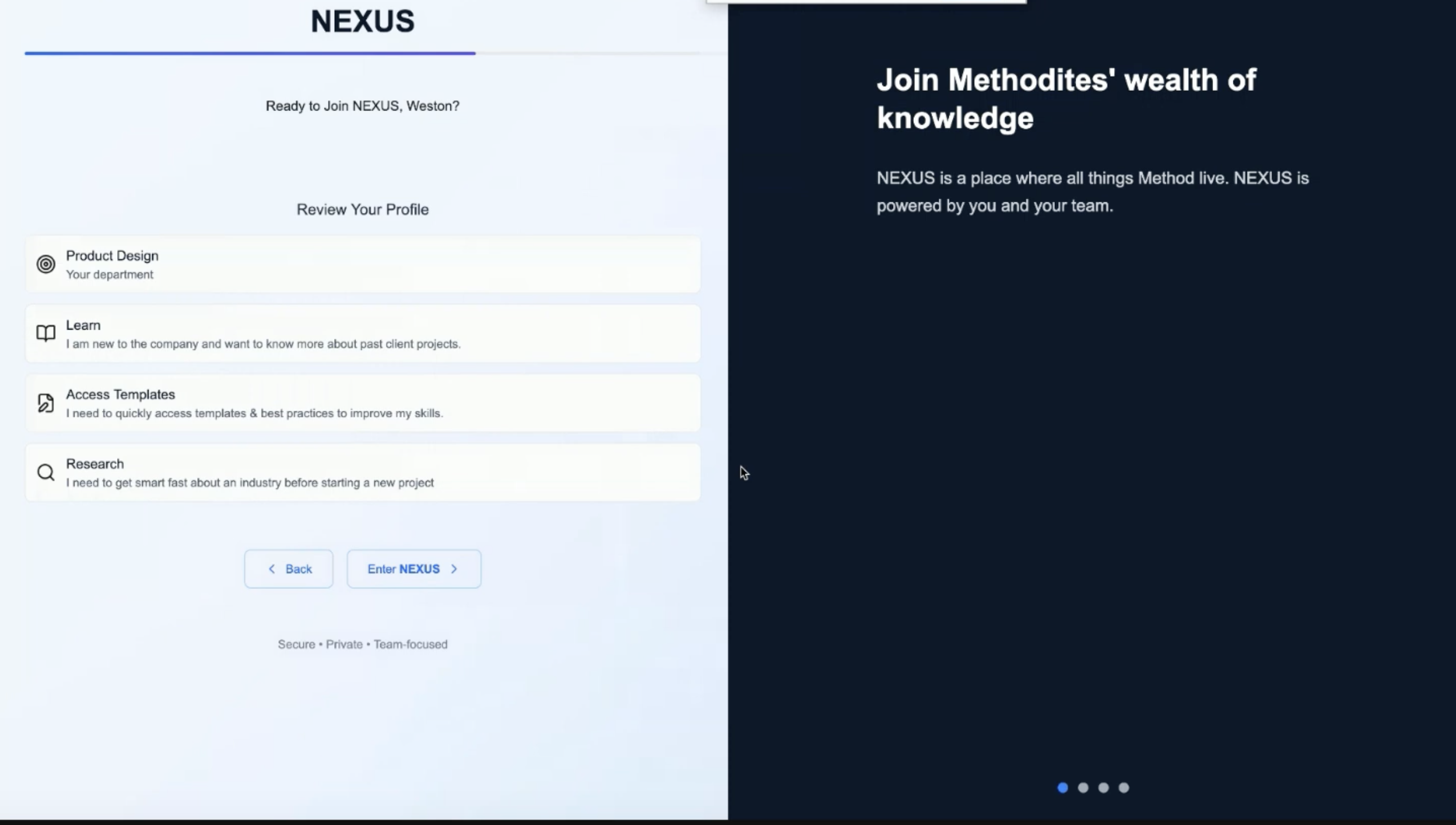

After authentication, NEXUS guides you through a structured onboarding flow that establishes your organizational context and preferences. The process captures your team affiliations, project responsibilities, and content interests to personalize your experience from day one.

Search & discovery

The main interface centers on universal search with intelligent defaults. Results appear as cards showing key metadata (Content Type, Project Phase) with hover actions that deep-link directly to source files. Users can toggle between card and list views for different scanning patterns.

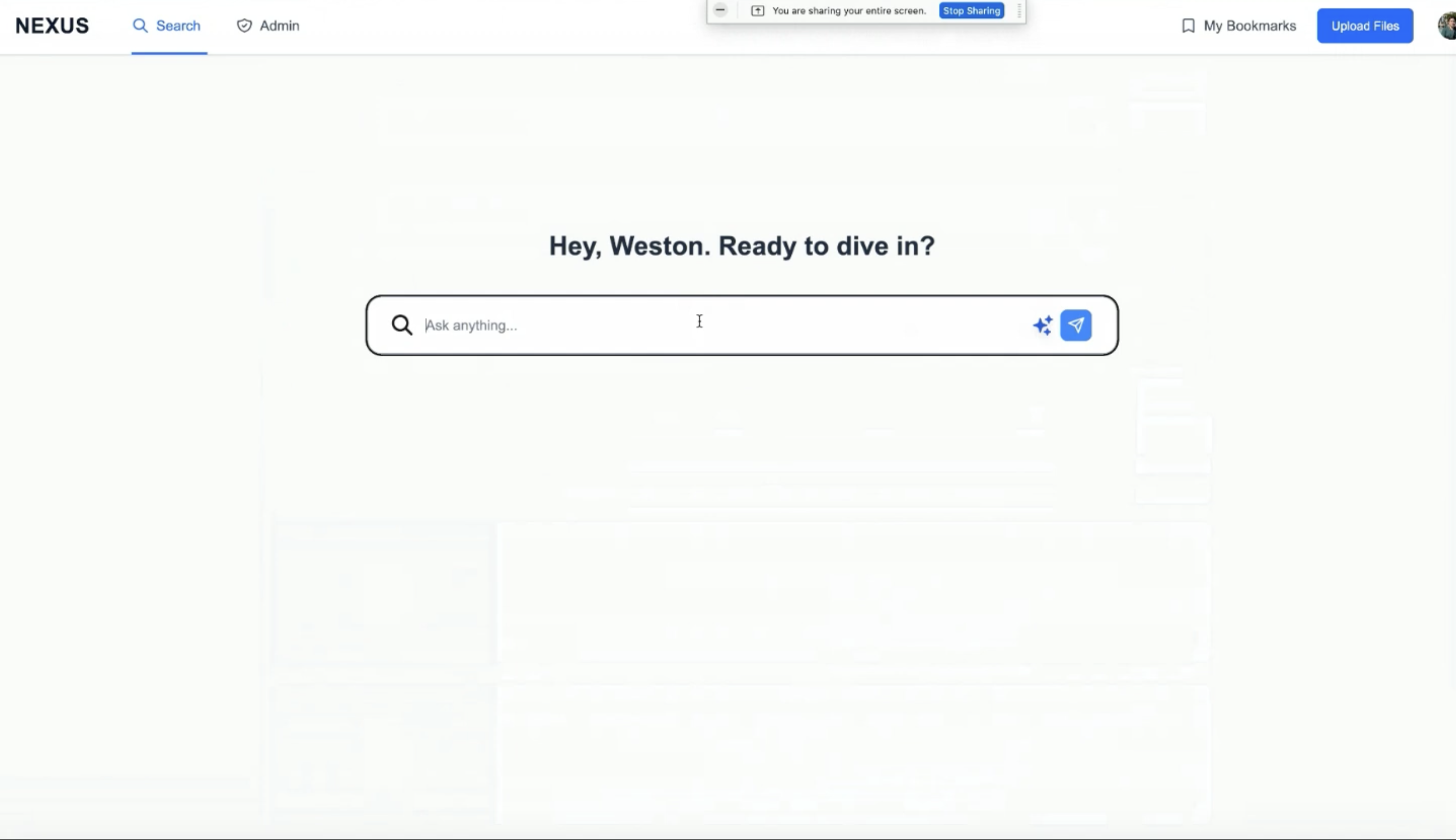

Conversational search

Beyond traditional keyword search, NEXUS includes a chat interface that accepts natural language queries. For the MVP, this processes queries through keyword extraction and matches against the same underlying search infrastructure, allowing users to ask questions like “show me strategy documents from the Nike project” in conversational language.

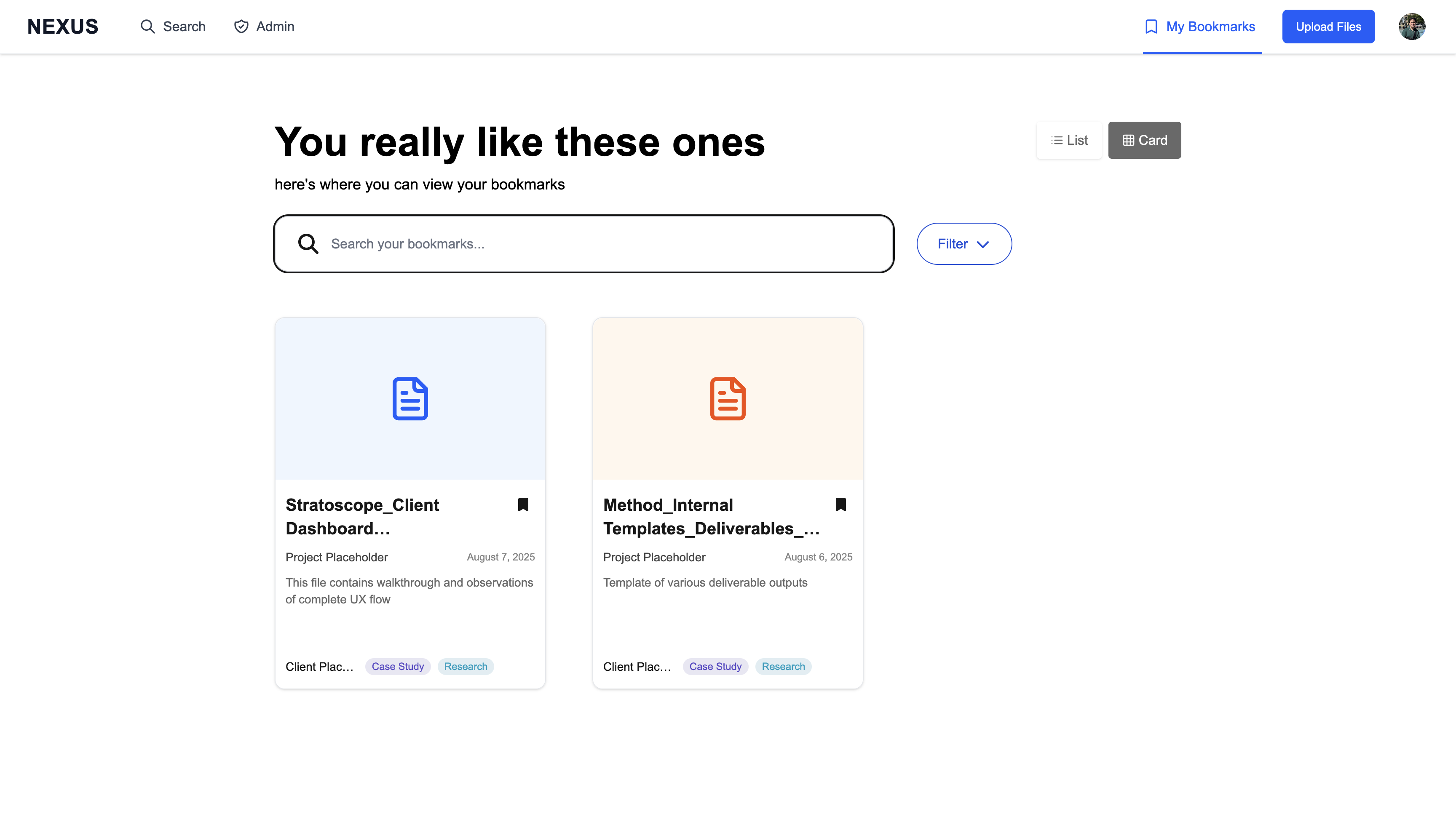

Personal organization

Any search result can be bookmarked for later reference. The bookmarks page mirrors the main search interface, so saved items remain filterable and searchable—avoiding the “bookmark graveyard” problem.

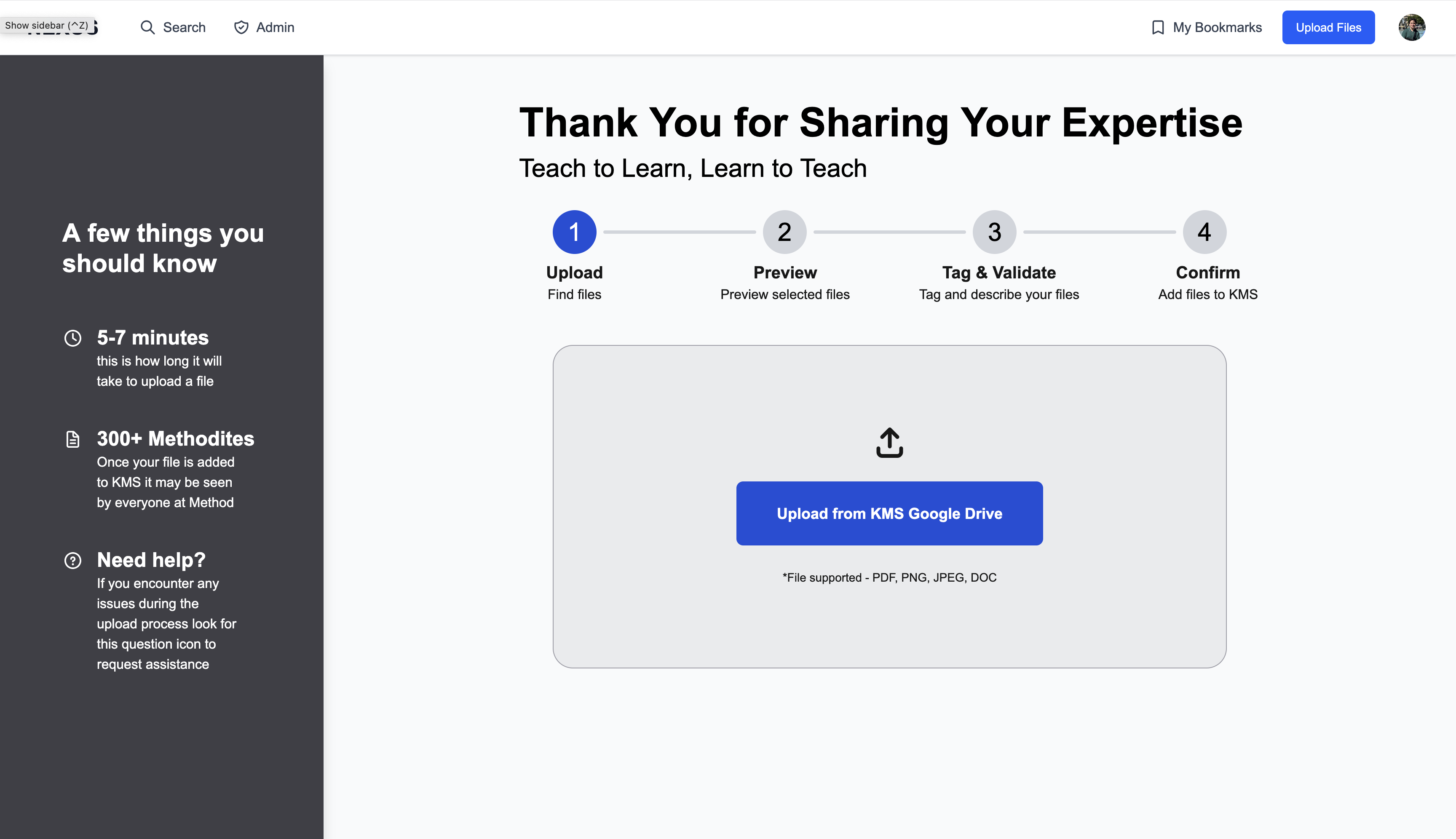

Structured contribution

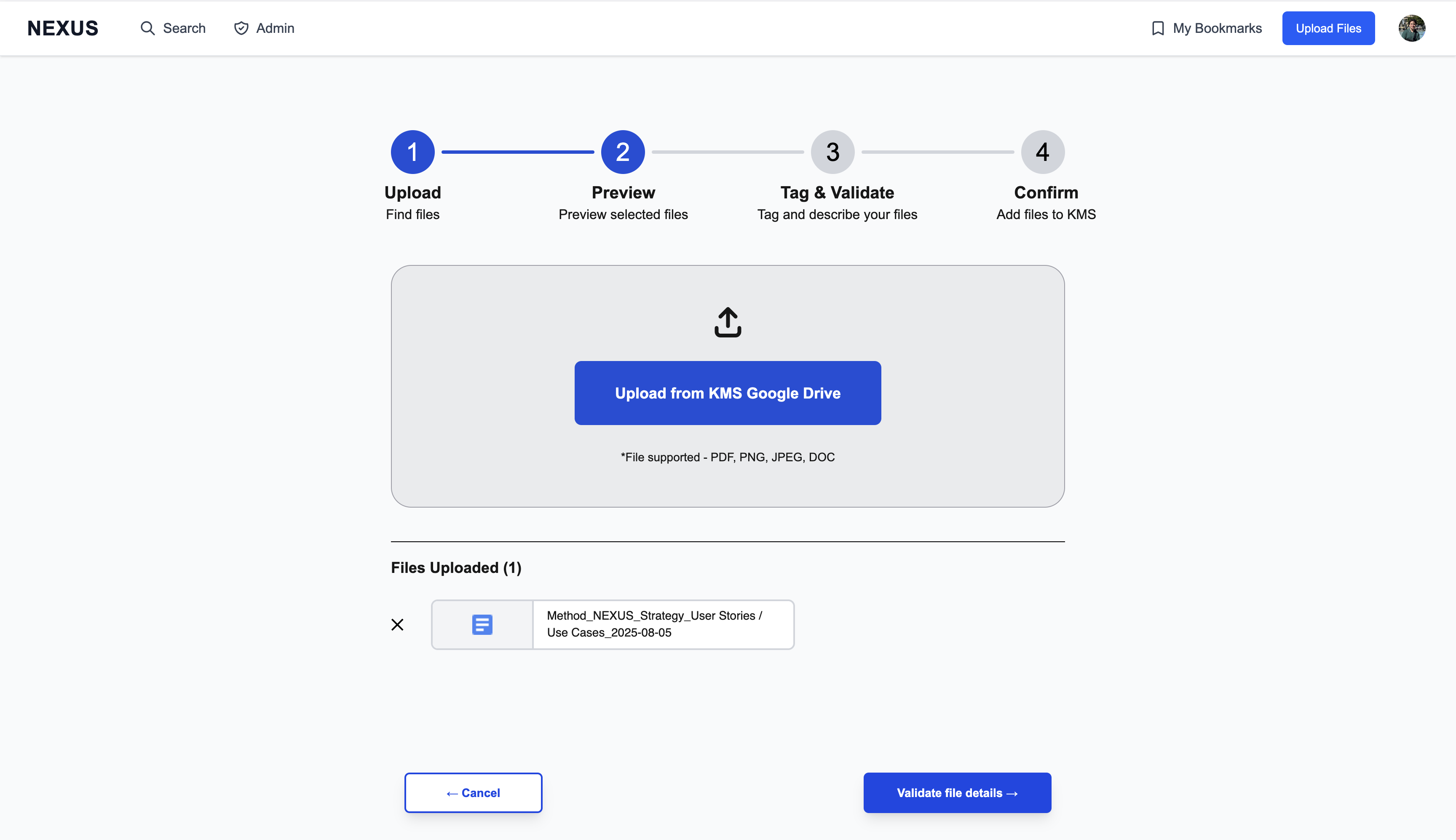

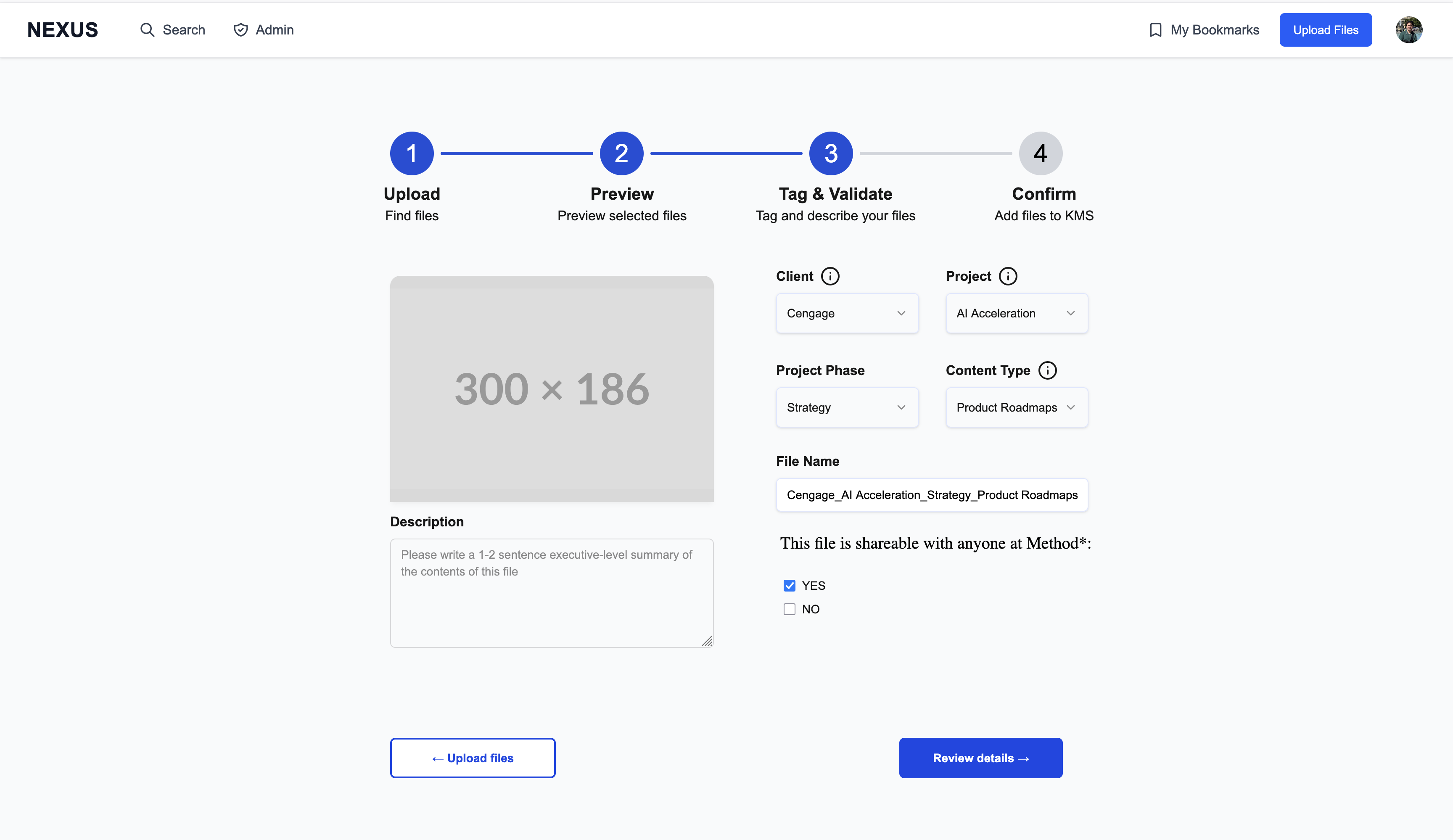

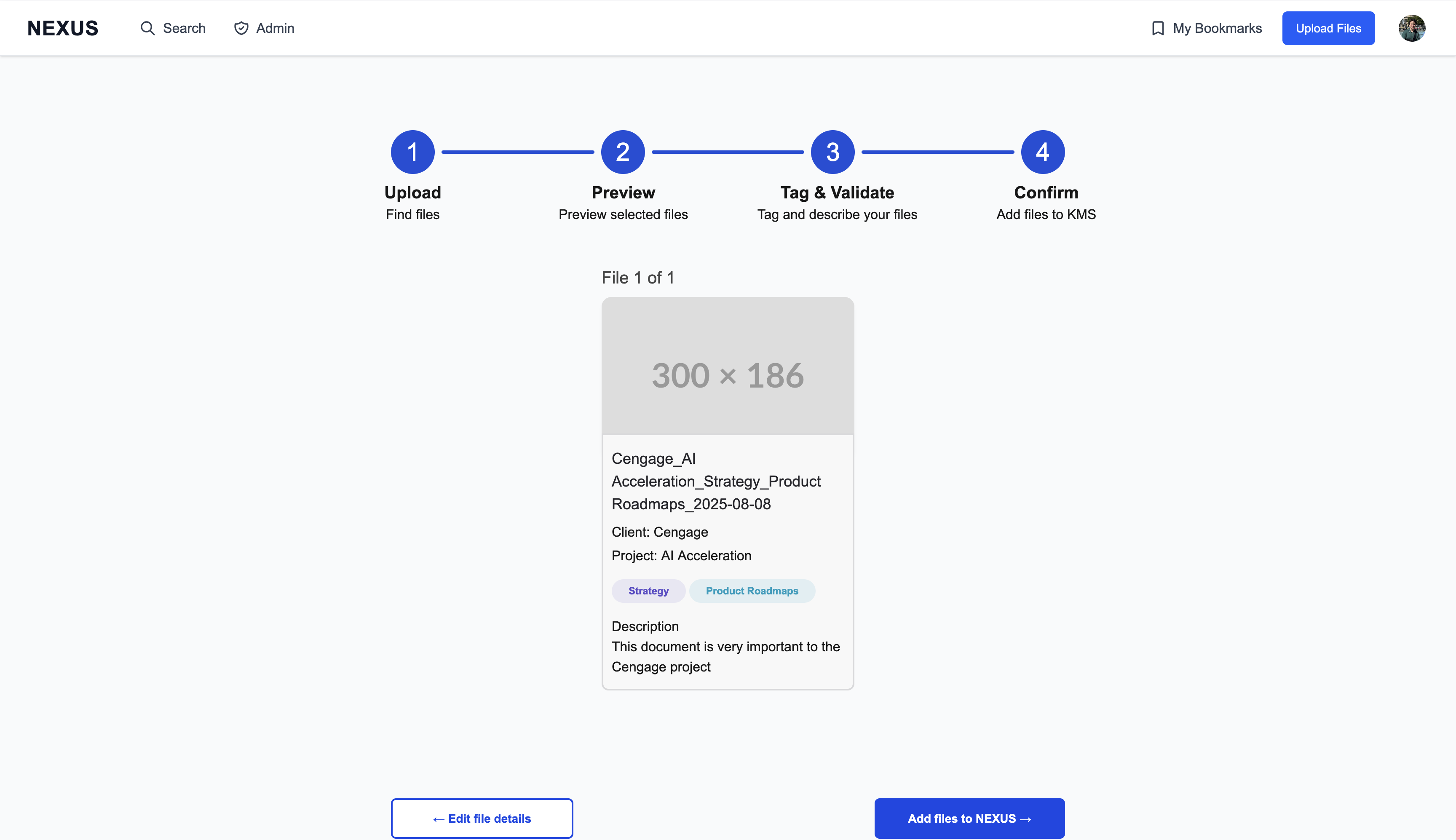

Content upload follows a deliberate four-step flow designed to ensure quality metadata:

- Select files via Google Drive picker

- Preview your selections

- Tag & validate with required metadata (Client, Project, Phase, Content Type, description)

- Confirm and see exactly how the content card will appear

The interface shows inline validation errors and includes a shareability toggle for org-wide visibility control.

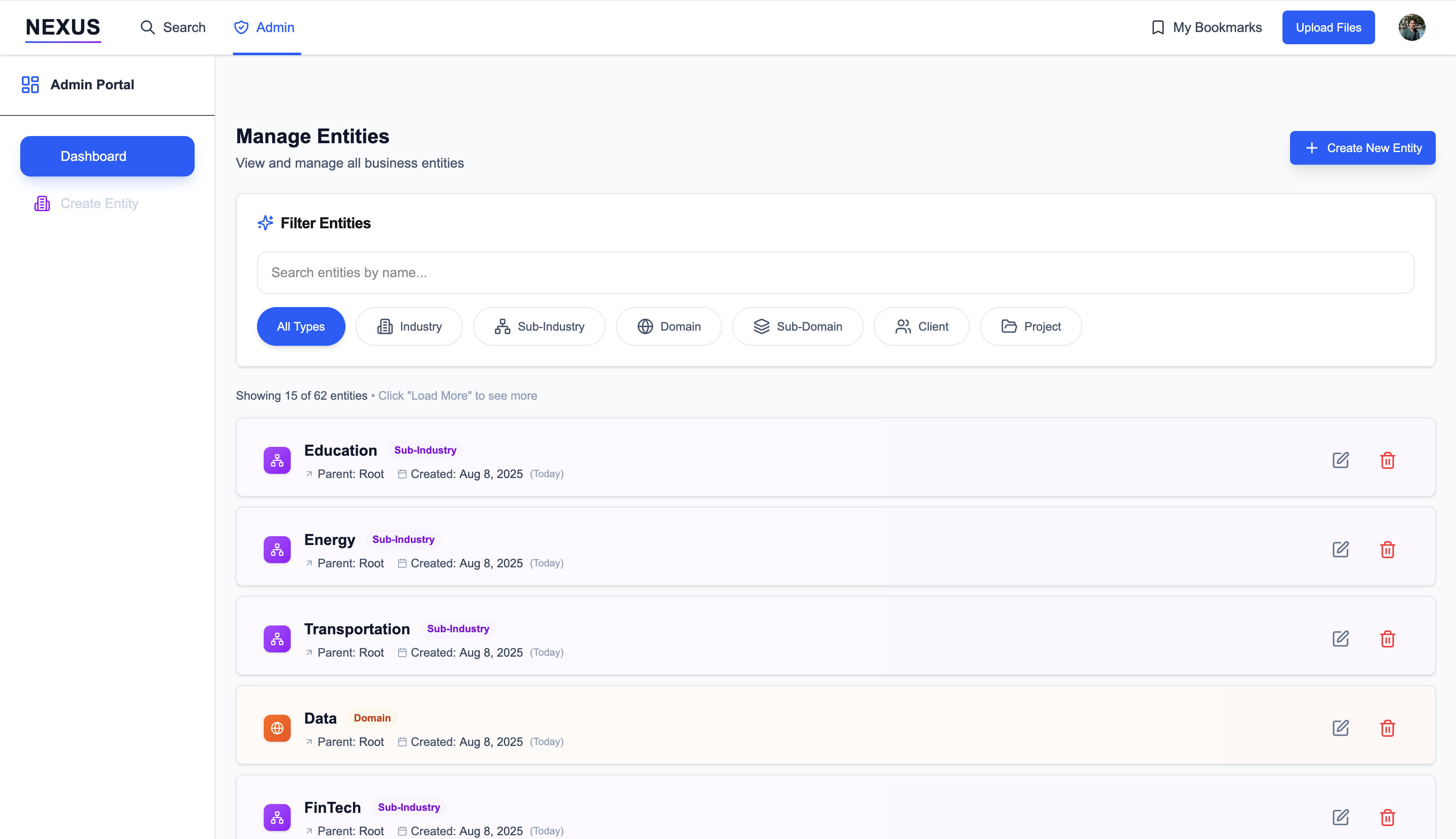

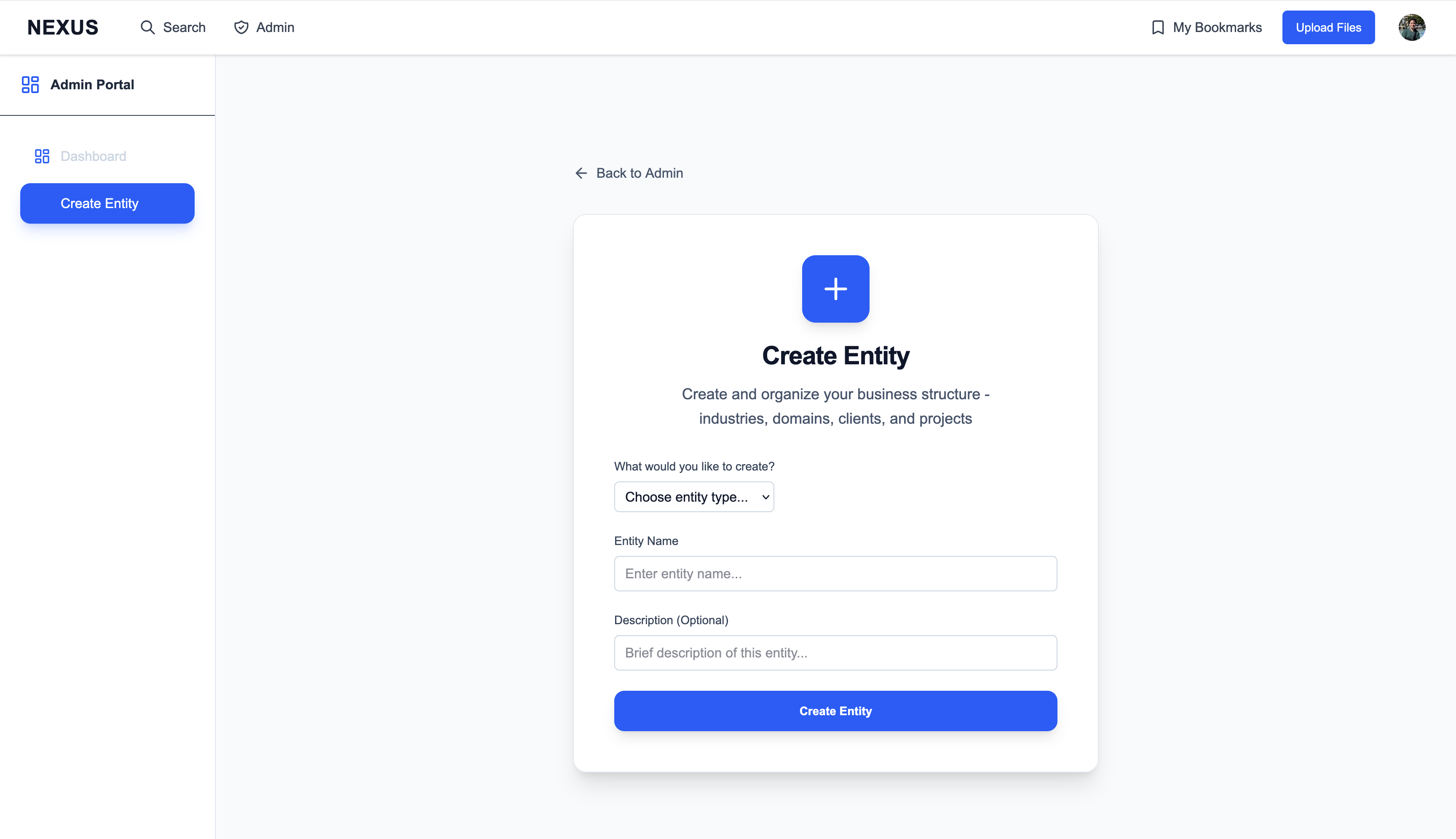

Admin capabilities

For system administrators, NEXUS includes entity management interfaces for maintaining organizational structure and metadata consistency.

Architecture: deliberately small, deliberately fast

Every technical decision came down to a simple question: what gets us to a working MVP fastest while maintaining enough quality to demo confidently? The answer shaped an architecture that prioritized deployment simplicity and developer velocity over theoretical purity.

We built on Next.js 15 with static export, which meant zero server configuration and instant global deployment through Firebase Hosting. The styling system combined Tailwind for rapid iteration with Radix components for accessibility—no time to build design systems from scratch. Authentication stayed simple: NextAuth handled app sign-in with Google, while Drive operations called REST endpoints directly from the browser, eliminating any SDK dependencies that would force us into server-side execution.

The data layer centered on Firestore, which gave us real-time updates and complex querying without database administration overhead. Every choice traded some theoretical best practice for practical shipping speed. Under normal circumstances, client-side Drive token management would be questionable; under a three-week deadline with corporate restrictions blocking backend deployment, it was the only path forward.

Security approach & tradeoffs

Security decisions under time pressure require uncomfortable honesty about what you’re willing to accept. We made two significant compromises that would raise eyebrows in a normal development cycle, but were defensible given our constraints.

The first was client-side token management. Google Drive tokens lived entirely in browser memory with 1-hour expiry, no backend refresh mechanism. This exposed us to XSS attacks and meant users had to re-authenticate hourly, but it kept us on static hosting and let us ship without server infrastructure. We documented this explicitly in ADR-0002 (see below), outlining the exact risks and our post-MVP migration plan to proper backend token handling.

The second compromise was our permission model. Rather than building complex permission-aware filtering, we copied uploaded files to a shared NEXUS space visible to all authenticated users. Not the long-term approach, but it let us demo meaningful content discovery without weeks of authorization logic. Again, we wrote this down clearly—technical debt is manageable when it’s visible and planned, dangerous when it’s hidden.

Data model & performance

The data model had to balance simplicity with the complex filtering requirements that made NEXUS useful. We settled on three core Firestore collections, users, files, and folders, that could handle both real-time updates and the multi-dimensional queries users needed.

Users held everything from basic identity and team membership through onboarding preferences and personal bookmark collections. Files became the heart of the system—linking Drive metadata with our business taxonomy (client, project, phase, content type) while maintaining searchable descriptions and technical details like MIME types and file sizes. Folders mirrored the Drive hierarchy but added cached metadata to keep searching and filtering fast.

The real complexity came from search performance. Users expected to filter simultaneously by client, project, industry domain, phase, and content type—all while maintaining sub-200ms response times. We pre-built 63 composite Firestore indexes to support every combination, trading write amplification for read speed. In a knowledge management system, users read far more than they write, so the tradeoff made sense.

Search & retrieval strategy

Search had to feel instant while handling complex business logic that users couldn’t see. We built a layered system that kept the simple cases fast while supporting the sophisticated filtering that knowledge workers actually need.

The first layer handled facet filtering on the server—client, project, industry, domain, phase, content type—always ordered by recency since fresh content matters most in knowledge management. But server-side sorting wasn’t enough; users needed relevance ranking that understood their intent. So we added client-side scoring after the initial fetch: phrase matches in titles got the highest weight, individual keywords throughout content added smaller bonuses, and excessively long filenames took a slight penalty.

Pagination stayed stable through cursor-based paging using the last server document, which meant the list wouldn’t jump around even after client-side re-ranking. TanStack Query handled caching with filter-specific keys, so switching between “Strategy” and “Implementation” phase filters felt instant.

The chat interface reused this same infrastructure but accepted natural language queries. For the MVP, this meant keyword extraction rather than semantic understanding—we consciously deferred LLM integration and embeddings to avoid needing backend infrastructure that would slow our deployment cycle.

Delivery mechanics: two sprints, plus prep

We ran two 5-day sprints back-to-back. Each began with a ~2-hour planning session across all 13 team-members: PMs produced features and user stories, we assigned owners and points (powers of two), and we paced scope accordingly. The Jira board flowed Backlog → In Progress → Design sign-off → PM sign-off → Complete. Midway through Sprint 1 we split tickets into Lo-fi / Hi-fi / Backend lanes so engineers could build against Lo-fis while Hi-fis matured.

I front-loaded most backend-adjacent work before Sprint 1, which made the sprints feel “front-end heavy” even though the real time sink was admin entity creation—the system that let administrators create and manage organizational entities (clients, projects, content types) that users could tag content with. This required synchronizing Firestore metadata with Drive folder structures while maintaining consistency and handling partial-failure rollbacks when operations failed midway. In retrospect, I’d avoid this complex data mirroring at MVP and accept “link-only” uploads first.

We retired three risks early: (1) app + Google auth, (2) baseline file creation (Firestore metadata plus Drive copy), and (3) admin entity creation (late Sprint 1 / early Sprint 2).

Team dynamics & management realities

Recruiting mid-program challenges

Pulling six engineering interns mid-program created both opportunities and friction. Most were finishing their Tech Dash rotations and understandably hesitant to switch projects with just weeks remaining. The transition required program leadership intervention and careful communication about learning opportunities in a compressed timeline.

Some strategies worked well: pairing newer interns with myself and other interns who had more technical experience accelerated onboarding significantly, and I invested upfront in clear documentation and setup guides to reduce day-one friction. Setting up development environments in advance meant interns could start contributing code immediately rather than spending their first week on configuration.

However, I consistently underestimated the knowledge transfer overhead with intern-level experience. I assumed they could immediately contribute to complex features without extensive guidance, and I didn’t establish clear coding standards and review processes from day one.

Skill alignment and the pivot decision

The interns’ web development background (React, TypeScript, modern tooling) strongly influenced our Chrome extension → web app pivot. While this created some initial architectural debt, it ultimately accelerated delivery since we could leverage their existing intern-program training rather than teaching extension-specific APIs and deployment processes from scratch.

What we learned

The biggest lesson: discovery and engineering work better in parallel than in sequence. Starting technical spikes in weeks two or three to validate risky assumptions—auth scopes, API quotas, hosting constraints—would have surfaced integration issues early rather than during the final sprint.

On a personal level, I ran 80+ hour weeks during the final push. This intensity was a conscious choice—I wanted to prove myself and completely devour the challenge in front of me. While not sustainable as a permanent working style, it was the right decision for an opportunity where I could demonstrate what I was capable of accomplishing.

If we had two more weeks

Detangle storage: switch to Firestore-only metadata + links; defer Drive copying to a background job behind a Cloud Function.

Automated tagging: extract likely client/project/phase/content type at upload time; confirm in the Tag & Validate step.

Chat quality: add lightweight semantic retrieval and LLM re-rank with request timeouts; move token refresh server-side to enable this safely.

Permissions: begin surfacing “what you can actually access” by default (no shared-copy crutch), starting with least-privileged scopes and a thin proxy.

Roadmap (gated by a tiny backend)

Phase 1 (stabilize): minimal backend for token refresh and Drive ops; permission-aware surfacing; basic analytics (User_Events, Search_Contexts); enforce CI gates.

Phase 2 (discoverability): semantic retrieval + re-rank; automated tagging; recommendations seeded from onboarding + usage.

Phase 3 (breadth): multi-source indexing (Figma, Miro, Confluence), versioning, referability workflows, controlled external sharing.

Conclusion

NEXUS proved that you can ship meaningful knowledge management tools under extreme constraints—but the real lessons emerged from the process itself. We demonstrated that discovery-heavy approaches can work in compressed timelines, provided you’re willing to run technical validation in parallel rather than waiting for perfect requirements. The pivot from Chrome extension to web app, while stressful in the moment, ultimately delivered a more extensible foundation that users actually enjoyed using.

The technical choices—static hosting, client-side Drive integration, Firestore-powered search—weren’t always elegant, but they were honest about our constraints and transparent about their tradeoffs. We documented every compromise, making technical debt visible rather than hidden. This approach let us ship a production system that Method’s teams actually adopted, with fast search across thousands of documents and an upload flow that enforced the metadata discipline necessary for long-term discoverability.

Perhaps most importantly, NEXUS highlighted the human dynamics that make or break ambitious projects under pressure. Managing a team of six interns while personally contributing the majority of the codebase required intense personal commitment. The 80+ hour weeks during the final push were a conscious choice—I wanted to prove myself and completely devour the challenge, delivering something I was genuinely proud of rather than just meeting minimum requirements. While this intensity isn’t sustainable indefinitely, it was the right call for an opportunity where I could demonstrate what I was capable of accomplishing.

Looking back, NEXUS succeeded not because we avoided mistakes, but because we made our constraints and tradeoffs explicit from the beginning. We shipped a real product that solved a real problem for real users, and we wrote down everything we learned along the way. In a residency program designed for rapid experimentation and learning, that combination of delivery and documentation represents the best possible outcome.

Role note

I served as Technical Manager: set the architecture, bootstrapped the repo and pipelines, wrote the initial large slice of code, recruited and onboarded engineers, ran two sprints to completion, and shipped the MVP—navigating hosting constraints, a mid-program product pivot, and a compressed delivery window.

Appendix A — ADR-0002: Client-Side Drive Integration (excerpt)

Context: MVP must list/search user Drive files; corporate rules block short-term server code.

Decision: obtain user-scoped tokens in browser; call Drive REST client-side; store tokens in memory; accept 1-hr expiry + re-auth.

Pros: zero backend, fast delivery. Cons: XSS exposure, no silent refresh, client-side rate limits.

Follow-ups: small backend for refresh + sensitive operations; hardening checklist.

Appendix B — Firestore search details (v1)

Facets: client, project, industry/domain, phase, content type.

Indexes: 63 composite indexes to keep any combo fast.

Ranking: phrase boosts, per-keyword bonuses, long-name penalty; aggregate score sort.

Paging: cursor via last server doc (stable under re-rank).

Caching: TanStack Query, short TTL recommended.

Appendix C — Sprint structure & board

Two 5-day sprints; Friday pre-planning (~2h) with the full team. Jira states: Backlog → In Progress → Design sign-off → PM sign-off → Complete. Mid-sprint refinement: Lo-fi / Hi-fi / Backend lanes so engineers could build off Lo-fis without blocking on Hi-fis.